Antisocial media

To defeat online abuse once and for all, Areeq Chowdhury and Tess Woolfenden ask whether we should suspend social media platforms.

Upon his election as Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn famously promised to usher in a new form of kinder, gentler politics, but is it achievable given the lucrative nature of confrontation in this digital age? Can individuals change the course of online debate and put an end to abusive behaviour on the internet and in society, or is radical reform required?

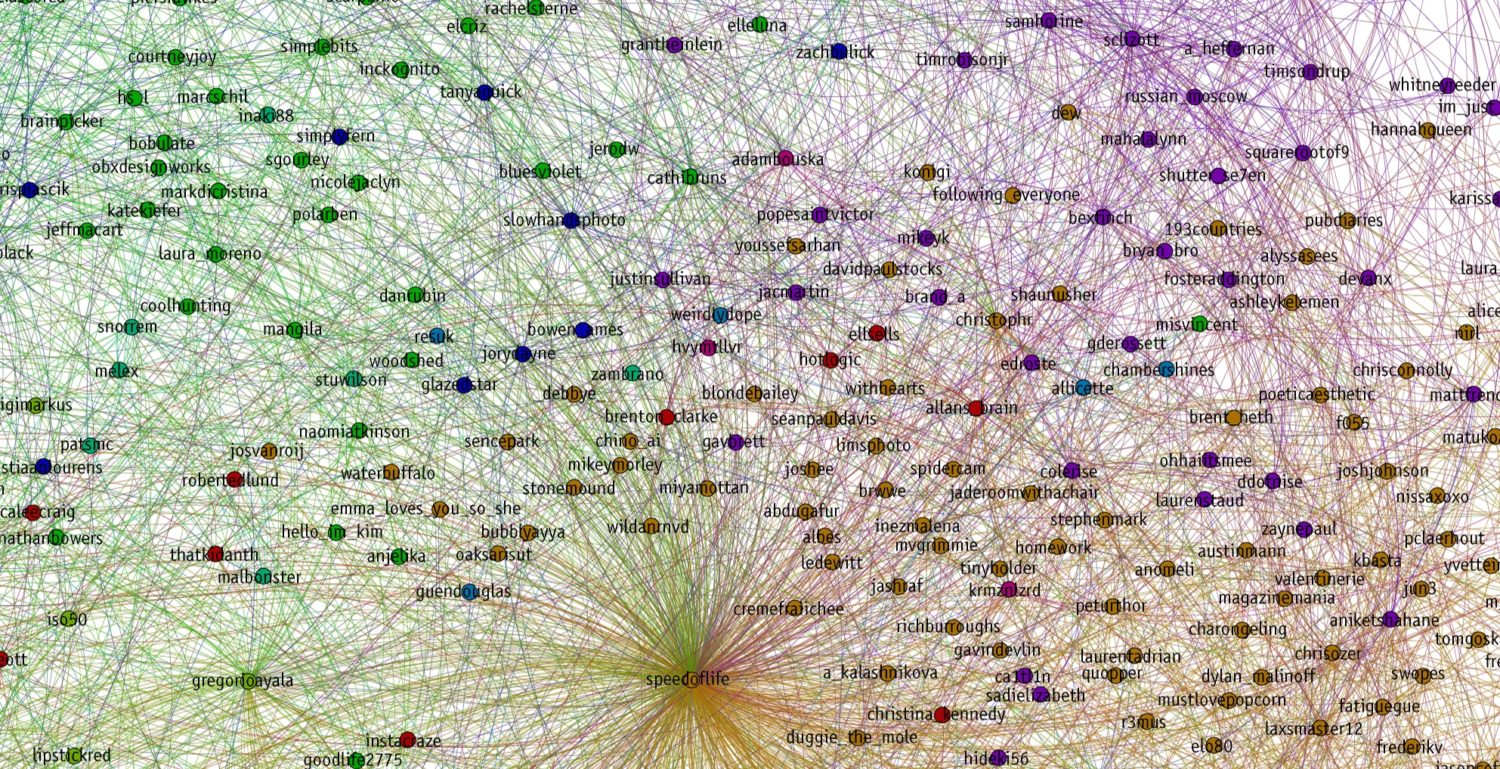

Online abuse is an ever-increasing concern for those engaged in the political sphere. WebRoots Democracy’s recent analysis of more than 53,000 tweets revealed that there are twice as many negative and abusive political conversations than positive ones, with a huge number of users experiencing abuse in one form or another when sharing their views online – this was especially true of young women and ethnic minority users. What arose as a great beacon of free speech and open debate has unfortunately descended into a sewer of hate and abusive content.

The effects can be hugely damaging for victims and their families, causing stress, trauma and in some cases fear for safety and the need to seek police protection. But the impact of online abuse also has the potential to be damaging for democracy, and society more widely – it often pushes people out of political forums as users opt-out, self-censor or are encouraged to shut down their accounts in the interests of personal safety. Given that it is often women and minority groups who are the most targeted, online abuse has the potential to seriously undermine political representation in the UK. So, what can be done?

Social media companies derive greater benefits than we do from our use of their platforms. With it should come a requirement to ensure it is a safe and civil space for users. The status quo solutions are heavily tipped towards retrospective action with the responsibility often falling on the shoulders of users themselves. Report, mute, block. None of these actions do anything to prevent abuse in the first place and it’s hard to imagine they can ever have any significant impact in the long-run.

The solutions in existing literature put forward thus far have largely been mild, uninspiring, and lacking in ambition. Now is the perfect time for radical, yet practical, reforms – such as the introduction of ‘platform suspension powers’. These powers, requiring the input of parliament, the judiciary, an independent regulator, and internet service providers, would block specific social media websites from operating in the UK for up to three days. It would act as a final sanction by the state to reprimand social media companies that consistently fail to significantly tackle hate speech on their platforms.

Countries around the world which have introduced nationwide bans of social media websites in the past include Bangladesh; China; Egypt; India; Iran; Malaysia; Mauritius; North Korea; Pakistan; Sri Lanka; Syria; Tajikistan; and Vietnam. The fact that many of these countries contain autocratic governments and that decisions were often taken to close down political opposition has rightfully cast a shadow over the potential of blocking social media platforms. However, would it be different and could it work in a more democratic society with due process, such as here in the UK?

In London last year, the ride-sharing tech giant, Uber, had their licence revoked by Transport for London for failures in corporate responsibility. Whilst this decision was widely criticised in the media and amongst many users, it was a rare display of the enforcement of local laws by a regional authority upon a major player in Silicon Valley. The proposed ban was lifted once Uber made a number of ‘far-reaching changes’ to their policies on safety and security. Would a similar approach work with the likes of Facebook and Twitter, or has their evolution from social networks to social infrastructure rendered them out of bounds?

For the state to effectively protect citizens online, the powers to temporarily block social media platforms in circumstances of endemic, unaddressed hate speech could act as an important final sanction for regulators in the UK. It could represent a new, more effective, incentive for social media companies to ensure their websites do not become safe harbours for hate preachers. It would also definitively shift the responsibility for cleaning platforms of abuse onto the collective shoulders of states and social media companies; away from the ordinary, individually powerless, user. Radical – yes. Practical – maybe. Worth consideration – why not?