What now for Labour?

We are living in uncertain times. The tectonic plates underpinning politics are shifting dramatically. When Francis Fukuyama proclaimed that the 'end of history' had arrived in 1992, you would have been forgiven to think he was onto something: global capitalism...

We are living in uncertain times. The tectonic plates underpinning politics are shifting dramatically. When Francis Fukuyama proclaimed that the ‘end of history’ had arrived in 1992, you would have been forgiven to think he was onto something: global capitalism – buttressed by liberal ideals of formal equality and the uninterrupted flow of capital and labour across borders – appeared to be on a path to reign supreme. Irrefutably, the politics of globalisation defined the roadmap for parties everywhere. Today the future is hazy at best, impenetrable at worst. It would be a fool’s errand to take part in this kind of political divination nowadays.

The uncertainty of present times means stomaching an uncomfortable, to some an unpalatable, truth. The Labour party is a construction, the result of variegated interests converging through time. It is a product of history, not a timeless entity with a God-given right to exist. Just as we formed a hundred years ago, we can just as easily cease to exist. Those that say that as a result of the crisis engulfing our party we will be out of government for a generation are wrong. They fail to entertain the idea we may never return to power.

To my mind, present circumstances raise three main challenges for the Labour party and the Left more broadly. First, Brexit has unleashed a new politics which stands at odds with many of our core values. It is a politics of turning inwards and away from the world, a politics which sees few qualms with erecting barriers between ‘them’ and ‘us’. Our new Prime Minister seems happy to embrace it. But how we engage with Brexit Britain whilst remaining true to our progressive, internationalist ideals seems less obvious. How do we, for example, untangle legitimate concerns about levels of migration from the sometimes xenophobic undertones accompanying those articulations? Taking the former seriously whilst closing down any space for the latter is not straightforward. The two discourses (xenophobia on the one hand, concerns about migration on the other) can reinforce one another in complex and indeterminate ways.

A second related challenge is “pasokification” – the phenomena of the break-up of social democratic parties in times of austerity. A recent poll by Opinium and the Social Market Foundation found that whilst Conservative voters are relatively united, voters on the Left have a more fragmented outlook. A chasm seems to be opening between the so-called ‘metropolitan Left’ and our traditional working-class base. On the one hand, urban groups – think Islington and Camden – hold a distinct set of values: they are very socially liberal, comfortable with open borders, and want to protect the welfare state. On the other hand, working class voters – in particular in the north and the midlands – are more socially conservative, sceptical of migration, and critical of benefits. To become a political force to be reckoned with, we have to find a way of speaking to both these groups. This is a formidable task, perhaps an impossible one.

A final challenge is the changing nature of work. In the mid-twentieth century, the Labour party had an obvious go-to social constituency. The factory and places of mass employment united workers through shared daily experiences; through trade unions in the workplace and the Labour party in parliament workers would find representation. Those days are of course long gone. Ever since the 1980s, the labour market has been changing rapidly. But the flexibilisation and individualisation of labour is reaching new heights. In the UK, one in seven of us are now self-employed, and in the US 50 per cent of people will at least in part be freelancers by 2020. In these conditions, what does it mean to be a party of labour? How can we represent a vision of solidarity when the bonds connecting workers are few and far between?

These are big challenges. There is no easy answer, no silver bullet. To rise up to them we will have to summon every inch of creativity and political skill we can muster. We will have to display a level of agility we have never had to before. With clinical precision and brutal honesty, we will need to dissect the political landscape so that the opportunities and constraints facing the Left can be understood with absolute clarity.

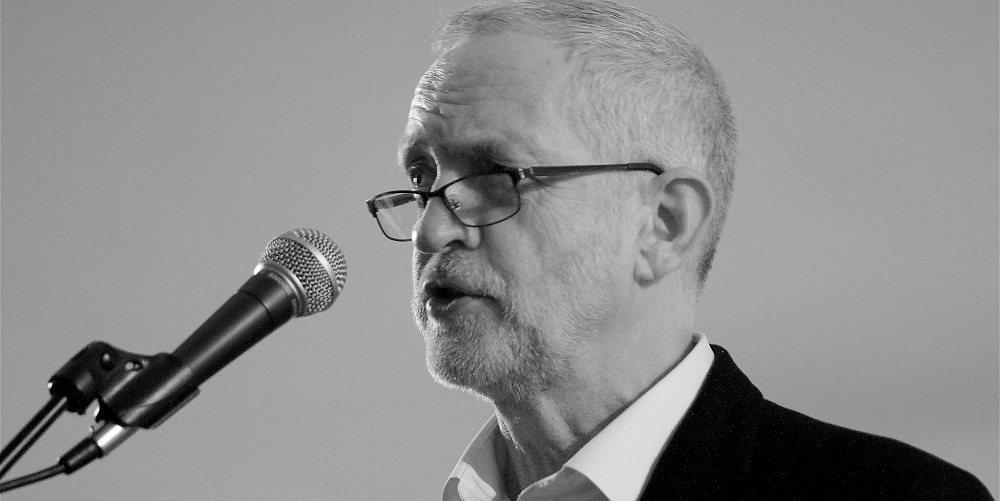

The first step must be to unite and stop all of this internal bickering. It is disappointing that yesterday David Blunkett opted to go on the offensive against Corbyn. We need to get behind the leadership – the membership has spoken loudly and clearly. People want a change of direction. They want a party that asks big and searching questions about the shortcomings of neoliberalism and its effects: massive inequality, insecurity for far too many, a world shaped more and more by unaccountable elites and less by ordinary, working people.

Whilst Corbyn’s critics need to change their ways, the leadership also needs to step up to the mark. Corbyn in particular has to begin to demonstrate leadership qualities he has to date palpably lacked. He needs to show he can think beyond the prism of his own political ideology and build bridges within the party. He and his team also need to begin speaking to the electorate in ways that make sense to people who don’t identify as being on the Left. That means stepping outside of their comfort zone and viewing the world from a radically different perspective – from the perspective of people to whom ideals like ‘social justice’ and indeed ‘socialist values’ mean very little.

Despite the uncertain nature of our times, and the deep, deep challenges that lie ahead, there is plenty to be optimistic about too. Jeremy Corbyn has energised our party in a way no other leader has arguably done before. Labour is the biggest party in Europe, if not the world. Our members are to date an untapped asset. Mass rallies must now be converted into a mass political movement. All of this is possible. Uncertainty means possibility as much as it means risk. We can begin to shape a new political reality if only we unite and begin to face the profound challenges which lie ahead.