Tragic consequences

Frances Ryan draws much-needed attention to the human costs of austerity, as Simon Duffy explains.

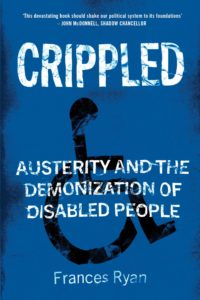

I was radicalised by austerity, and I remain astonished that so many others seem not to have been. Recently, talking to an old friend and fellow member of the Labour party, I found he was more outraged by Brexit than by austerity and was even thinking of joining the first incarnation of Change UK. Crippled, a powerful book by respected journalist Frances Ryan, is the perfect wake-up call for anyone similarly sleepwalking through austerity.

I was radicalised by austerity, and I remain astonished that so many others seem not to have been. Recently, talking to an old friend and fellow member of the Labour party, I found he was more outraged by Brexit than by austerity and was even thinking of joining the first incarnation of Change UK. Crippled, a powerful book by respected journalist Frances Ryan, is the perfect wake-up call for anyone similarly sleepwalking through austerity.

Crippled integrates moving human stories with an array of facts and data to demonstrate the vicious harm caused by the post-2010 cuts. It describes how disabled people are the primary target of welfare reforms, savage cuts to local authority funding and the collapse of legal aid. It throws the impact of these policies into harsh and painful relief, through the testimony of the disabled children and adults who are being pummelled by government cuts.

Statistics are more powerful than just numbers when you realise the reality behind them is malnutrition, homelessness, debt, physical and mental illness, prostitution, young children caring for their parents, women who cannot afford to flee domestic violence, suicide and unnecessary deaths. Austerity kills and it is killing disabled people. Ryan does a brilliant job of describing the human costs.

As Ryan explains, part of the reason that the UK government has got away with what it has done is that disabled people are not seen as equal citizens. While some disabled people, like Stephen Hawking for example, are idolised for ‘overcoming’ their disability, too many people are pitied or shamed for ‘failing’ to do so. Worse, as economic times get tougher, and the powerful seek to distract us, disabled people have been turned into a perfect scapegoat group. The rise of disability hate crime, fuelled by political and media rhetoric, reveals the shabby moral fabric of modern Britain.

Ryan ends the book on a hopeful note, believing the austerity tide is finally turning; and John McDonnell, who has been a consistent ally of disabled people through these dark times, says that the book ’should shake the political system to its foundations’. But I am left wondering whether our system has any foundations worth the name.

For austerity is also the story of the complete failure of the political system and of civil society to protect the human rights of disabled people. The United Nations has published several critical reports describing flagrant abuses of human rights in the UK. For instance, Theresia Degener, chair of the United Nations’ committee on the rights of persons with disabilities, has told the UK government that its cuts to social security, social care and other services had caused ‘a human catastrophe’. But the government shrugs off each criticism and the media and civil society quickly move on to the next issue.

It is also worth remembering that, particularly between 2010 and 2015, the Labour party often found itself supporting welfare reforms ‘in principle’ – and that many of those coalition reforms were themselves prefigured by New Labour policies. The infamous ‘benefit thieves’ campaign was an effort by New Labour to appear tough on benefits, but it has played directly into the hands of those wanting to stigmatise poor and disabled people. Benefit fraud was, and remains, statistically insignificant, but when good people fail to resist lies and injustice they risk legitimising them.

Also striking has been the failure of civil society to resist austerity effectively. Despite cuts which have seen, for instance, 44 per cent fewer people receiving adult social care, there has been no powerful and organised campaign to resist these cuts. Local government, the church and charities have sometimes issued critical statements, but they tend to understate the crisis, and after a little flurry, everything goes quiet again. The strongest resistance has come from grassroots organisations like Disabled People Against the Cuts. It is perhaps no coincidence that the best campaigning comes from those not dependent on government funding.

Austerity should end our faith in an inevitable law of social progress and encourage us to question whether the powerful will always act for the common good. If we want to build a society with a real commitment to social justice then we are going to have to focus on making it much more difficult for politicians to exploit people’s fears and prejudice.

We also need to put the protection of human rights – including social and economic rights – at the heart of our legal system. It is essential that we restore the integrity of civil society and reduce its dependency on political patronage to ensure that the voices of those harmed can never be silenced again.