Rising together

Labour must not see the world through a middle-class lens, argues Andrew Harrop.

There have always been professional voices within the British left; the Fabian Society itself is proof of that. But the centre of gravity of the Labour party used to lie firmly with working-class Britain. Since the 1990s that has gradually changed as the make-up of Labour voters, members and elected representatives has gentrified.

A forthcoming Fabian report will show how this is playing out in the nation’s political geography. The constituencies with the most working-class voters have been steadily drifting away from Labour, while those with the most professional voters have been increasing their support. At the 2017 election, Labour still won most working-class seats in England and Wales. But the party was barely ahead of the Conservatives in terms of total working-class votes; and it was behind when it came to skilled blue collar electors.

Meanwhile, within the Labour party, the battles between Corbynites and moderates have largely been between two rival tribes of professionals and largely over their preoccupations, be that Europe, university tuition or the onward march of social liberalism. We must not become class-blind.

Traditionally, Labour’s professional wing never dismissed class. Indeed, it was the unifying theme in Labour’s 20th century political ideology, as the party shifted its attention from collectivism to egalitarianism. Tony Crosland, whose centenary falls this year, led that revisionist turn. In the 1952 New Fabian Essays he wrote ‘the purpose of socialism is quite simply to eradicate [the] sense of class, and to create in its place a sense of common interest and equal status’. He argued that the British left should aim to eradicate the divisive feelings of an unequal class-based society, not just measurable economic inequality. This is what marked out British social democrats from American left-liberals: Crosland was Rawls with class.

Looking forward, Labour’s future is at risk if it can only see the world though a middle-class lens. For example, the left must exercise great care when it promotes social mobility and equal opportunities to reach the top. Progression is the lived experience of most Labour MPs, who come from working-class homes but are graduates themselves. By contrast Labour politicians who started on the shop-floor are an endangered species, with too few call-centre and social care workers replacing the miners and ships’ stewards of old.

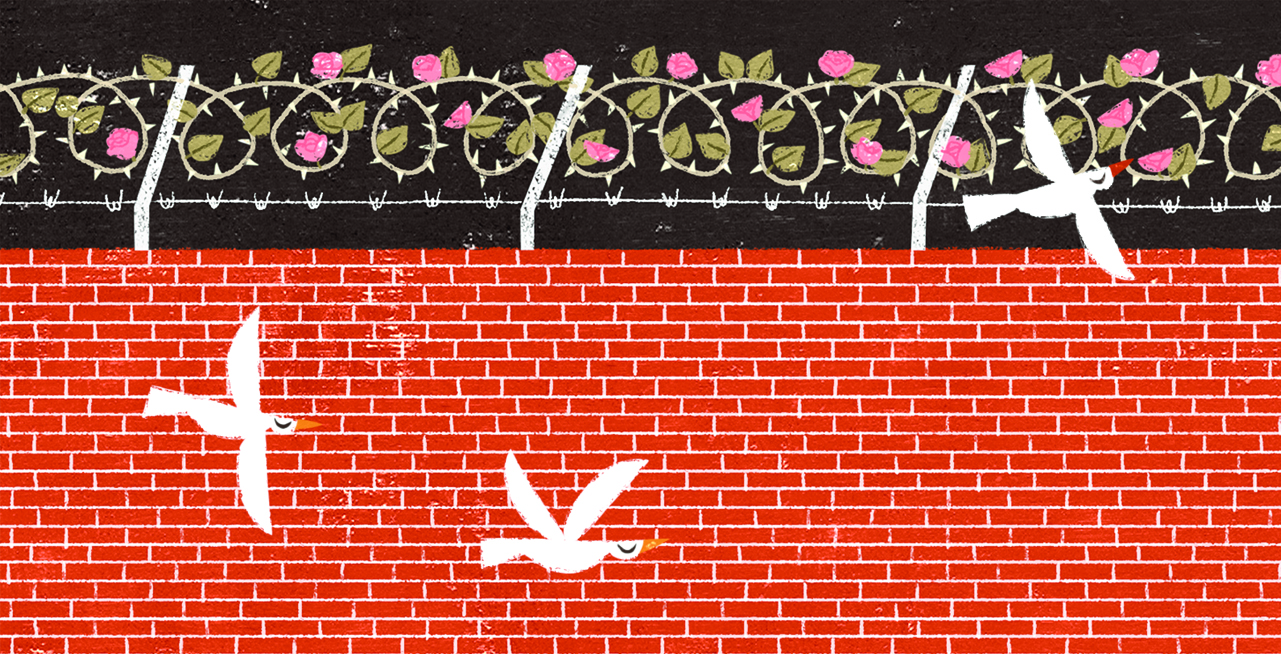

In their absence we risk forgetting that what matters is for entire communities to rise together, not for a lucky few to escape. Of course, people from every background are ambitious for their children. But the left’s mission is not to create more affluent urban liberals, it is to reduce the inequalities that create barriers between whole communities. Labour must devote its energies to enhancing the quality of work and education for people in ordinary jobs, in ordinary towns; to tackling their anxieties and building their power and social standing; and to improving their living standards, homes and public services.

To do that the left needs to be of working-class Britain not just for it, with more politicians who have not been to university. As things stand many working-class voters look at Labour and see another branch of the professional public sector establishment, telling them what to do. Recent controversies about the renewal of housing estates are a case in point. I have no doubt that Labour councils have been seeking to act in the best interests of their working-class tenants. But when they sound like technocrats not pavement politicians they fail to bring people with them. The change the left brings must be by and with working-class communities, never just for them.