Progressives in the pandemic

Demands being made during the Covid-19 crisis can shape our post-pandemic world for the better, argues Donatella della Porta.

On 24 April, Fridays for Future carried out its fifth global strike for environmental protection and against climate change. Due to the pandemic, the event was transformed into a digital strike. Lasting 24 hours online, it had 214,000 views in Germany alone. Via digital assemblies, activists discussed their programme and imagined a response to the pandemic through the affirmation of social and environmental justice.

Four days before, on 20 April, in Phoenix, Arizona, nurses dressed up in scrubs and surgical masks to block traffic in silent protest against Donald Trump supporters who were demanding an end to the lockdown.

And again in the US last month, Amazon workers staged a strike by calling in sick as Covid-19 swept the company’s warehouses. They were also denouncing Amazon’s attempt to discourage collective action by firing those who speaking out against the lack of health and safety.

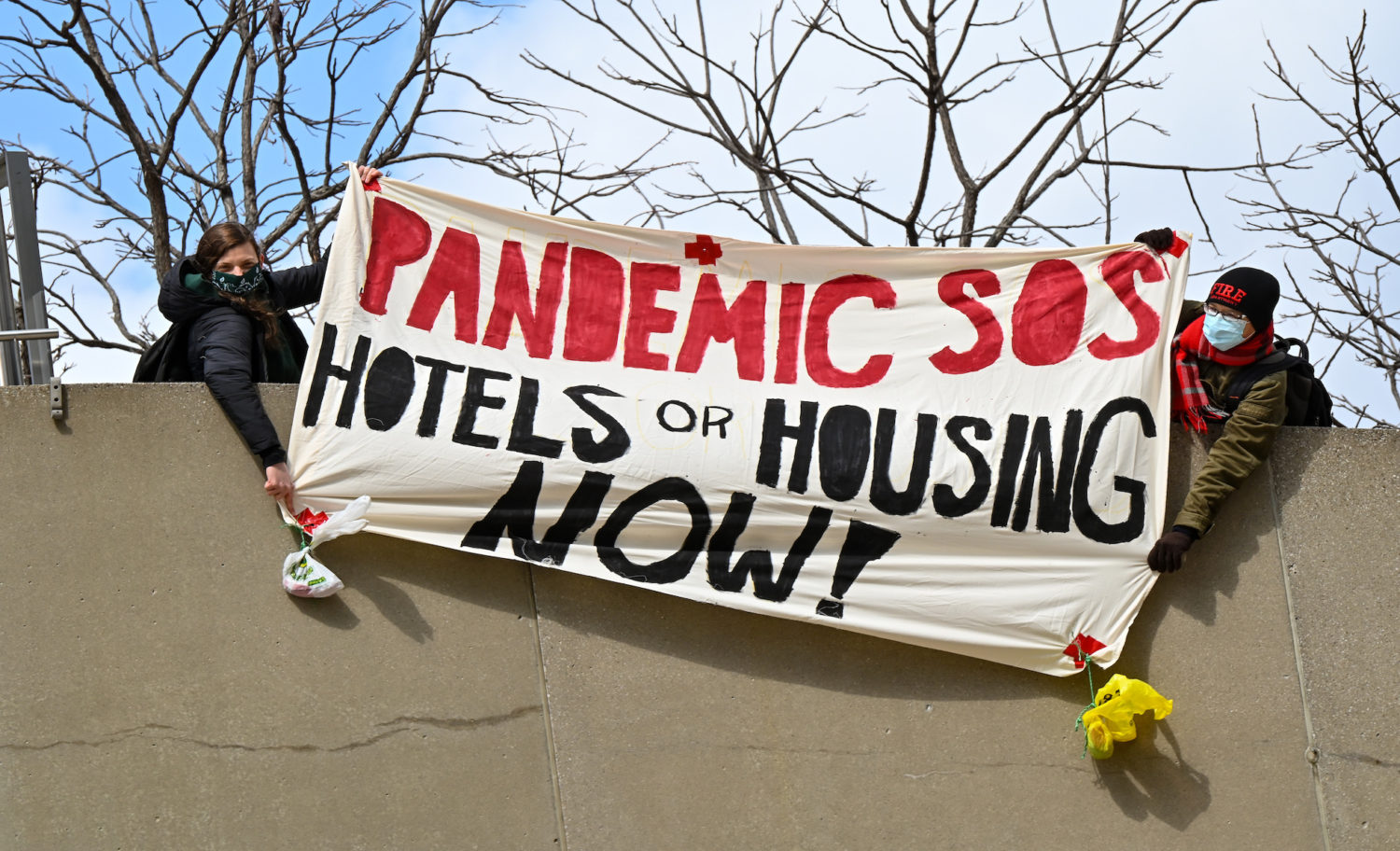

These are just a few examples of a largely unexpected new wave of protest during the Covid-19 crisis. The pandemic, spreading fear of contagion and the lockdown measures which have reduced the very possibility of physical movement, could have jeopardised collective action. But citizens are finding innovative ways to put forward their collective claims.

In some countries, healthcare workers are demanding structural changes to better protect citizens, such as in Italy, where 100,000 doctors signed a petition to strengthen their healthcare system. Elsewhere, workers of the gig economy, including riders, Uber drivers and call-centre workers have been mobilising in ‘wildcat strikes’, walking out of workplaces and staging flashmobs to call for protection against contagion as well as broader labour rights. Car caravans, cacelorazos from balconies, live-streamed performances and discussions, digital rallies, virtual marches, boycotts and rent strikes have multiplied as a way to denounce what the pandemic has made all the more evident and all the less tolerable: the depth of inequalities and their dramatic consequences on human life.

As in ‘normal’ times, protests during the pandemic are putting pressure on decision-makers by using, in different mixes, a logic of numbers, to show the spread of support for their proposals (as, for example the digital global strike called for by Fridays for Future), a logic of damage, by creating economics costs for companies (as with Amazon’s workers), as well as a logic of testimony, with activists proving the extent of their commitments through forms of action that imply personal risks and costs (as in the vigil of the nurses standing for patients’ rights, in front of abusive right-wing militants).

Visible protest is not the only way in which progressives are protesting. By organising online teach-ins and creating digital resources, activists are disseminating hyper-specialised scientific information on Covid-19 in an accessible way to increase democracy and participation.

Progressives are also are building on social movements that formed after the 2008 financial crisis.

The humanitarian crisis and years of austerity which followed the financial crash highlighted the limited capacity of political institutions (let alone the market) to intervene and bring support to those in need. In this time, progressive movements developed new forms of mutualism based on self-help groups, cooperatives and the production of alternative services — as in the traditions of the labour movement. Now, activists are using these networks to distribute food and medicine, produce masks and medical instruments, shelter the homeless and protect women from domestic violence. They are going well beyond charity by organising horizontally, providing services and spreading solidarity as the norm. It contrasts with the extreme individualism of neoliberal capitalism. This platform is another a form of political protest, with demands shifting from immediate relief to long term political and social change.

The pandemic has made ever more clear that we share a similar destiny, no matter which part of the world we live in.

Neoliberal capitalism weakened workers’ rights, with consequences that have become all the more dramatic during the pandemic. But progressive social movements are pushing for a post-pandemic alternative system which puts environmental and social justice at the centre, strengthens workers’ rights, improves labour conditions and combats inequality between generations, genders, ethnic groups and different geographical locations. As such, we are seeing claims developing for basic incomes, and better rights to education, housing and public health.

The pandemic has demonstrated the deadly consequences of weak welfare states (as evident across Europe and in the US), commodified health services and the devastating impacts of cuts to public health services. Covid-19 has also made evident the lethal effects of health inequalities, as the virus has hit the poor, ethnic minorities, old people and those in overcrowded housing much harder. The mortality rate has also been higher in more polluted areas, adding to the urgent need to address the climate crisis.

Besides the increase in the episodes of violence against women, the pandemic has also made blatantly clear both the importance of care activities and their unequal gender distribution with heavy burdens falling on women.

The pandemic has exposed the cracks in society – and has led to new ways of thinking and doing. It has enabled people to experiment with different systems, and new social relations are being built. It prefigures a different future.

Times of deep crisis can therefore trigger the invention of alternative but possible futures – though admittedly this does not happen overnight. The pandemic has drastically changed everyday life. It has created space and time to reflect on the post-pandemic world we want, that breaks significantly from the one before.