Making history

Continuing our special on the climate crisis, Tobia Charles considers past examples of market interventionism and what they can teach us to ensure the Green New Deal is a success.

Until now, politicians have found it difficult to brand environmentalism as a political ideology. As a result, they have struggled to frame economic questions in a way that avoids the same tired debates. But why is this? Possibly because on the one hand, emphasis on the existential threats posed by climate change quickly become overwhelming, while on the other, traditional cost-benefit analysis of the role governments play in tackling the issue produce unpopular policies, like carbon taxes. The distributional consequences of the latter approach have even lead to protests like the Giles-Jaunes seen in Paris.

The Green New Deal can be understood as an attempt to restock the political economists ideological tool-kit. A middle ground where one can simultaneously draw parallels with Franklin D Roosevelt’s transformative impulses hastened by the onset of world war two as an enabling crisis, but also redefine the responsibilities of government to intervene in the economy to bring about both social and environmental justice. Just like the New Deal, the Green New Deal prescribes a recognition that the only effective approach is an ambitious package of laws that reaches every sector of the economy. As a rhetorical device, it has proven effective. But you only need to take a quick look at the Democrats’ Green New Deal manifesto to see it is a brand that rehashes the aspirations of old movements to legitimise a fresh political mission and is certainly not a coherent plan.

The Green New Deal captures so well that understanding economics as a social system and not as a science speaks more to the structural issue of climate change, and that the reciprocal relationship of increasing global inequality and global warming is evidence of this. In terms of modern economic thought, proponents of the Green New Deal would consider themselves practitioners of political economy and not just economics. To them, the latter approach is little more than an empirical alibi for 21st century capitalism.

Conceivably, and within the context of our ecological crisis, political economists would look to history to draw inspiration for how market interventionism was justified in the past, and how the left might shape interventionist policy in the future. I want to focus on three historical implications you can identify from one statistic in particular: in 2007 the world consumed c.86 million barrels of oil a day, last year, it consumed c.99 million barrels of oil a day

The first is to do with industrial strategy. A key reason why oil prices have remained stable during this time of exponentially increasing consumption is due to the cheaper alternative of shale oil (acquired by fracking or horizontal drilling). The shale oil revolution was the seismic technological advancement in oil and natural gas production technology which only came about as the result of massive state investment during the 1970s. Back then, sharply rising oil prices in the Middle East led to recession and high inflation in the West.

Similarly, Richard Nixon’s “war on cancer” in the 1970s legitimised huge state investment in the National Institute of Health which paved the way for exciting developments in biotechnology bearing fruit even today. Even the digital revolution, which is only just beginning, can be traced back to world war two military spending and the Eisenhower administration. My point is that innovation is often indirect and history tells us that sweeping transformations can come as a knock on-effect of bold, persistent, experimentation. A self-fulfilling industrial strategy means enabling policymakers to take risks, freeing them from the cost-benefit analysis and short-term thinking that makes a spectator sport of today’s democracies so that our leaders can tell industry how it ought to change.

Second, the rise of shale oil occurred largely due to the cheap sources of capital made possible by quantitative easing and low interest rates. Since the financial crash, all of the money that central banks have printed through quantitative easing has led to venture capitalists supporting carbon intensive industries much to the neglect of green ones. Why is this?

It’s because we’re always assuming businesses want to become more sustainable, so we hand out green tax incentives in the hope that they will someday. But history tells us that industry-changing shifts come when the state exercises compulsory power to force corporates to co-create new areas of opportunity. In the 1920s, from fear of losing their monopoly status, AT&T reinvested their profits to create Bell Labs who went onto give us the laser, the PV cell (today used for Solar modules) and C++ programming.

A government that invests in green research and development programmes hopes to create a new market. In doing so, they are effectively socialising the risk that no market will be created. By the same logic, private companies who take advantage markets created by government research programmes without investing their profits back into research and development are privatising benefits made available by taxpayers. The Green New Deal should mean ending this market norm.

Third, this sharp increase in global oil consumption has occurred during a time where awareness about our destructive ecological effect also increased. In the public consciousness, increasing demand for oil is part of the story of global economic recovery since 2008. As a value system then, Gross Domestic Product is unable to account for the ecological feedback loops that result from how growth is determined. For the Green New Deal to be successful, it’s proponents must articulate a vision of growth that recognises averting climate change as a goal in its own right, and that means the language of sacrifice entering the Green New Deal political discourse.

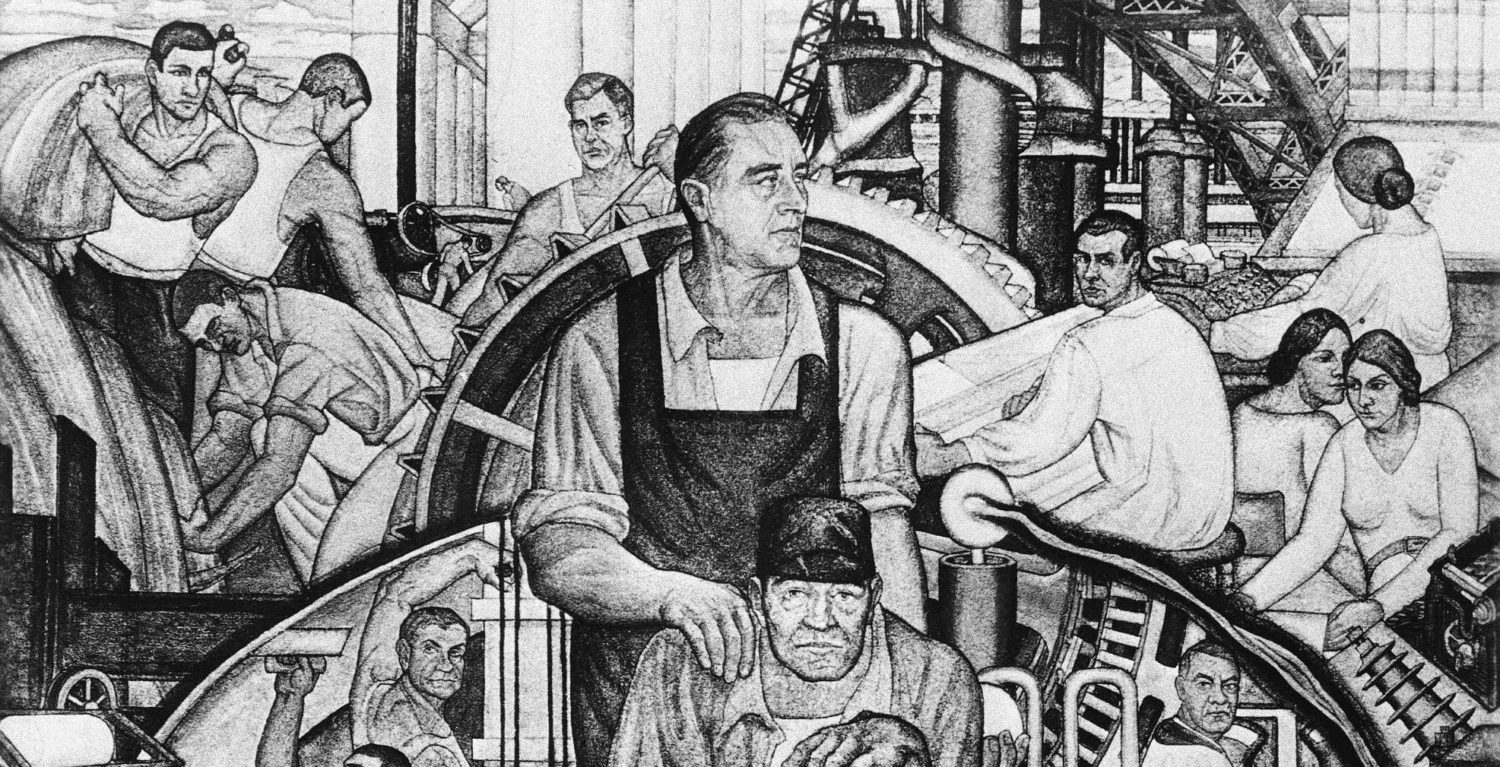

Photo credit: James Vaughan/Flickr