See no evil, do no evil?

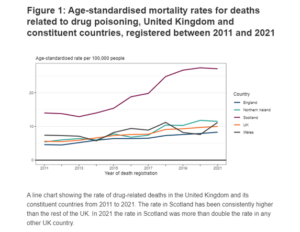

Dr Zack Hassan, writes on the SNPs politicisation of drug policy and its incoherent delivery of its own policy Scotland is facing an epidemic of drug-related deaths. Over 1000 Scots are dying every year, more than triple the next worst European country, and an avoidable tragedy.

Dr Zack Hassan, writes on the Scottish governments incoherent delivery of its own drugs policy

Scotland is facing an epidemic of drug-related deaths. Over 1000 Scots are dying every year, more than triple the next worst European country, and an avoidable tragedy. Despite the SNP’s efforts and expert consensus about the root causes, the so-called national mission to reduce drug deaths announced by Nicola Sturgeon in 2021 and published in 2022 has proved ineffective.

Progress on such complex issues obviously takes time, but the scale and persistence of Scotland’s deaths indicate that current approaches are insufficient. A comprehensive policy review and reset is urgently required to save lives.

It is not merely a failure of government, it is a moral failure. Behind every death is a son, a daughter, a shattered family: a blow to Scotland’s productivity which ripples to the next generation, passing on vulnerability to addiction. For too long, SNP ministers have had no satisfactory explanation for why so little progress has been made. Despite a comprehensive policy and record funding, delivery has been haphazard and incoherent. The reasons are clear: the underlying causes have been neglected, evidence-based practices have been inconsistently implemented, and crucial data collection has been inadequate. Other countries facing similar challenges, such as Portugal, can provide Scotland with a template of excellence. A policy reset would get us there in one decisive move, saving lives today and tomorrow in the process.

The continued rise in drug deaths is a clear sign current policies are inadequate. The National Records of Scotland showed there were 1,172 drug-related deaths in Scotland in 2023; a 12% increase on the previous year after two years of slight decreases.

Reassurances are now ringing hollow: “It is our duty to continue to prioritise the response to the drug death crisis so that the same cannot be said year after year,” said Public Health Scotland, yet deaths continue. The SNP may emphasise £250m of extra investment, but the British Medical Journal has found the outcomes underwhelming. Funding “may have contributed to the reduction of 279 deaths since 2021, but drug misuse is deeply embedded in the country’s most deprived areas.”

The question is not whether money has been spent, but whether it has been spent effectively. It is a moral imperative to know if it has been squandered.

While implementation is undoubtedly difficult, a policy reset would impact more successfully than the current approach. For example, safe consumption rooms and opiate agonist treatments have proven effective elsewhere but have not been consistently implemented in Scotland, in favour of residential rehabilitation, an unproven intervention. Funds could be better utilised if the SNP stops deviating from its own policy intentions, and prioritises interventions with immediate impact on the underlying causes: deprivation, mental health and harm reduction measures.

Some argue that it will take time to see the results of these interventions. But the issue is not one of patience—it is a matter of incoherence. Academics consistently identify socioeconomic factors as the root of the crisis, with the most deprived areas 16 times more likely to experience drug misuse deaths. Public health doctors give an equally clear message: “Tackling Scotland’s drug crisis requires addressing these underlying social determinants of health.”

While the SNP acknowledge this, you would be hard-pushed to find a concrete action within the National Mission’s annual report that has demonstrably tackled socio-economic inequality. One wonders whether direct interventions—such as cash transfers or targeted employment programmes—would have had more impact than anything that’s been done to date. The Mission’s Annual Report, designed to show the government’s progress, is full of woolly language and bureaucratic deflection: “In February 2023 we surveyed ADPs to understand what specific service provision currently exists for children and young people with emerging problematic drug and alcohol use.” This is not the language of urgency.

How long will Scotland wait before wondering if the problem is policy, not time? The 12% increase in deaths in 2023 suggests a failure of consistency, not a mere lag. Had proper action been taken to implement harm reduction, a dip in deaths should already have been seen. While some may oppose a policy reset, waiting for slow progress when the death rate remains this high is not morally tenable

Some choices by the government have been culpable. A focus on the immediate problem of deaths has come at the expense of prevention, the bedrock of longer-term reductions. The 2022 Scottish Health Survey removed a key question about drug use in the previous 12 months—a question that in 2021 revealed that 22% of 16-24-year-olds had used drugs. Given that one of the National Mission’s goals is to reduce the number of people developing problem drug use, it is astonishing that such important data is no longer there to provide a consistent way of knowing if government policies are having any effect.

Prevention and death reduction are not mutually exclusive; they must work in tandem. As a medical registrar, I have seen first-hand how critical prevention is: once someone overdoses and enters the hospital system, their chance of breaking the cycle without sustained intervention is slim. Future deaths should not be treated as less important, and urgent action to reduce drug use is required. A policy reset would restore prevention as a priority, ensuring that future waves of addiction are mitigated.

Even where evidence-based policies have been adopted, they have been implemented hesitantly. Experts argue that harm reduction policies such as opiate agonist treatments have been applied conservatively, with political considerations taking precedence over public health outcomes. One study notes that “guidelines and national policy documents remain guarded and revert to conservative dogmas rather than responding to the evidence, which should drive change… The politicisation of drug policy has contributed to the crisis of drug harms, and nowhere is this more evident than in Scotland.”

Experts are clear on why conservative instincts are misguided: tough sentences increase offending and drug use by disrupting drug users’ support networks, whilst seizing drugs increases the street price by reducing supply, increasing theft. Political and media criticism are challenges, of course, but Scotland’s inconsistent progress suggests a lack of commitment and moral leadership. A policy reset would provide the momentum to fully implement what works, demonstrating that the government prioritises public health over short-term political calculations.

Portugal offers compelling proof that the crisis is solvable. Its dramatic reduction in drug deaths came through a comprehensive approach that included rapid intervention and support services, as well as decriminalisation. Individuals caught with drugs were referred to a panel, where immediate action could be taken to address underlying issues like stress, unemployment, and trauma. Those who reoffended faced fines or had their licences revoked, ensuring accountability while avoiding the counterproductive consequences of imprisonment. The result? Fewer people became a drain on public services, and more citizens were rehabilitated before addiction took over their lives.

Instead, the SNP has taken a different lesson, focusing its policy energy on lobbying the UK government for decriminalisation—an area outside its competence—while neglecting the parts of the Portuguese model it could implement immediately. Some may assert that decriminalisation was central to Portugal’s success and that Scotland cannot replicate it without UK cooperation. While decriminalisation played a role, many of Portugal’s gains have resulted from holistic support and rapid intervention. Lobbying for decriminalisation can continue, and may even be more successful if Labour were in power at Holyrood, but such considerations should not delay immediate action on interventions within Scotland’s control.

The scale of drug-related deaths in Scotland is unacceptable. The SNP has laid a foundation, but its delivery is faltering and it is not achieving the necessary results. A complete policy reset is needed to break the cycle of stagnation. The underlying principles of the reset should be consistent implementation of evidence-based policy, rationalisation of metrics, immediate interventions on the underlying causes, and restoring the focus on prevention. These are not wishful ideas; they are effective actions to urgently tackle the crisis. Scotland cannot afford to lose more lives, nor should it accept a government that believes current efforts are sufficient. By embracing a comprehensive policy reset, Scotland will reject business as usual, and demonstrate the leadership needed to protect Scots from the harms of drugs.