Fighting the battle of ideas

Only transformational politics, such as we saw in 1945, can break Britain’s high inequality, high poverty cycle. Stewart Lansley explains

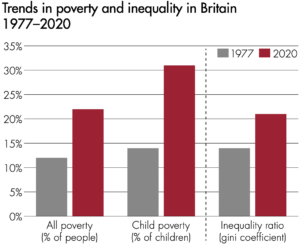

Since 1980, one of the most striking economic trends in Britain has been the surge in levels of both inequality and poverty. Among the world’s rich nations, Britain sits in second place – behind the United States – for inequality, and has one of the highest rates of poverty in Europe. We live in a society where poverty and inequality have become normalised.

That these two key measures of social fragility have moved in line with each other is no surprise. History could not be clearer: poverty and inequality are critically linked. Poverty occurs when sections of society have insufficient resources to be able to afford a minimal acceptable contemporary living standard. Its scale is ultimately determined by how the ‘cake is cut`. For much of the last 200 years, the process of private wealth building at the top has come at the expense of wider life chances, bringing not just a higher ceiling but a lower floor as well.

The last four decades represent the third wave of an embedded and ongoing flaw in Britain’s modern history: its high inequality, high poverty cycle. Unlike the business cycle which is common across capitalist societies, the inequality/poverty cycle is neither natural, nor universal. It is an artefact determined by the pattern and distribution of the structures of power. Poverty and inequality levels are ultimately rooted in the outcome of the political and economic power games that play out in company boardrooms, plush City offices and the corridors of Whitehall, and in the extent of popular resistance.

In recent decades, as in the period up to 1939, these factors have worked in favour of an over-empowered financial and corporate elite that has been unwilling to acquiesce to anything other than a token erosion of its muscle, privileges and wealth. Apart from the post-1945 decades – when the long poverty/inequality cycle was broken – a significant section of society has had to make do with the limited proportion of the proceeds of economic activity consistent with the needs of capital and wider political expediency and the self-interest of the wealthiest classes.

At the heart of these power games has been a process of ‘economic extraction’. Such extraction occurs when a small elite of capital owners is able to use its power to secure an excessive slice of the economic cake using business practices that have reverberated across economies and society, negatively affecting wage levels, working conditions, livelihoods, and community resilience.

The history of economic change has been one where the costs of upheaval, however necessary for economic progress, have been born most heavily by the weakest members of society, a group which also ends up with a limited share of the subsequent gains. The biggest winners from the industrial revolution were a small group of plutocrats – landowners and the new financial and merchant classes – who used their political and economic power to seize an excessive share of the undoubted gains from industrialisation. The same story has been repeated time and again. The Great Crash of 1929 and the state’s response wrought years of havoc and intractable poverty across industrial Britain. The fall-out from the rolling shocks of the past four decades – rapid deindustrialisation, globalisation, the 2008 financial crisis, austerity and now Brexit – have, as in the pre-1939 era, all been unevenly born in a way that has deepened existing divisions.

Despite Britain’s long poverty/inequality cycle, those who have had the biggest influence on the course of social history – the political classes, business elites, and mainstream thinkers – have mostly taken the view that poverty is a standalone issue, quite separate from the way the gains from economic and social progress are shared. They have simply dismissed or ignored the link between inequality and poverty, while egalitarians have only won the battle of ideas all too briefly.

In 1914, the historian and reformer, RH Tawney, argued that: “What thoughtful people call the problem of poverty, thoughtful poor people call with equal justice, a problem of riches.” Tawney had a big influence on the Labour party and its early egalitarian thrust. But the view that tackling poverty depends on tackling inequality and its roots has mostly been a minority one. His views were not shared by other social reformers of his time. Inequality was also a blind spot for Sir William Beveridge. It was not one of his five ‘giants’ that needed to be slain.

The post-war era of ‘egalitarian optimism` is as close Britain has come to implementing Tawney’s vision. When equality peaked in the late 1970s, poverty levels hit an historic low. But during that decade, the egalitarian school lost the war of ideology to a group of pro-inequality New Right thinkers who claimed – wrongly – that higher levels of inequality were necessary to drive economic progress. Keith Joseph, one of the key advisers to Margaret Thatcher, put it bluntly in 1976: “The pursuit of income equality will turn this country into a totalitarian slum.” As in the 19th century, this view soon became a key tenet of mainstream economics, taught in universities, promoted in boardrooms and parts of Whitehall and enacted by political leaders.

While creating a more equal society has long been Labour’s central purpose, the party has mostly been much less precise about what it means or how to achieve it. “The commitment of the Labour party to equality is rather like the singing of the Red Flag at its gatherings,” wrote the distinguished economist Sir Tony Atkinson: “All regard it as part of a cherished heritage, but those on the platform often seem to have forgotten the words.”

The last 40 years have seen a real life experiment in a model of inequality-driving capitalism that was meant to boost entrepreneurialism, with the gains trickling down to all. What has actually been at work is a form of levelling up at the top and levelling down at the bottom, a process that simultaneously sucks strength from the economy and is the enemy of wealth creation. The extractive power of today’s business barons, as in the 19th century, has allowed disproportionate rewards at the expense of others, from ordinary workers and local communities to small businesses and taxpayers, often by steering economic resources into unproductive use, with no or limited addition to economic value. “The efforts of men are utilised in two different ways,” declared the influential Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto in 1896: “They are directed to the production or transformation of economic goods, or else to the appropriation of goods produced by others.” Such ‘appropriation’ – as widespread today as in Victorian times – simply ‘crowds out’ activity that would yield more productive and social value.

It is no coincidence that today’s rich lists are full of wealth extractors – a mix of landowners, financiers, property tycoons, oil and private equity barons and tech monopolists – rather than wealth creators. Extractive capitalism has fuelled the surge in levels of poverty but also weakened the economic base and delivered greater turbulence. The evidence is clear. As shown by the International Monetary Fund, high levels of inequality are associated with weakened economic performance.

Today, with mounting evidence of the negative impact of excessive levels of inequality on economic stability, social resilience and individual life chances, politicians play lip service to narrowing social divisions. There is much talk of creating a better post-Covid society and speculation about a third ‘sea-change’ in political philosophy, away from the austerity politics of the last decade. But are we on the edge of a more fundamental change in direction or a mere political tweak, a temporary, pragmatic response to a national crisis? As Robert E Lucas, one of the Chicago-based high priests of the post-1980s market revolution, once observed about economic crises: “We are all Keynesians in a foxhole.”

A post-pandemic society can take one of two paths. It can retain today’s value-sapping and high-inequality system. Or it can be steered in a wholly new direction, one built around a different set of social values aimed at finally breaking Britain’s high-inequality, high-poverty cycle. This would require the kind of transformational politics of 1945 aimed at ending the built-in inequality bias of the current economic system. On current trends and policies, the odds are on the former. To deliver the latter, egalitarians need to win back the battle of ideas and quickly.