Expectation management

There is nothing inevitable about Labour winning the next general election, says Matt Singh.

Local elections aren’t the easiest things to interpret, with thousands of individual polls taking place in wards that vary greatly by geography, demography and politics. And especially when they take place at a time of political realignment, proponents of almost any narrative can point to a result somewhere that fits their story.

Because most of last week’s contests were in Labour areas, the raw vote and seat totals aren’t meaningful on their own. The best single metrics for each party are the estimates of how the whole of Great Britain would have voted if elections had been held in every ward. The BBC version, called the projected national share, put the two main parties level on 35 per cent each. The Plymouth University measure, known as the national equivalent vote, gave the Conservatives a narrow (37-36) advantage nationally.

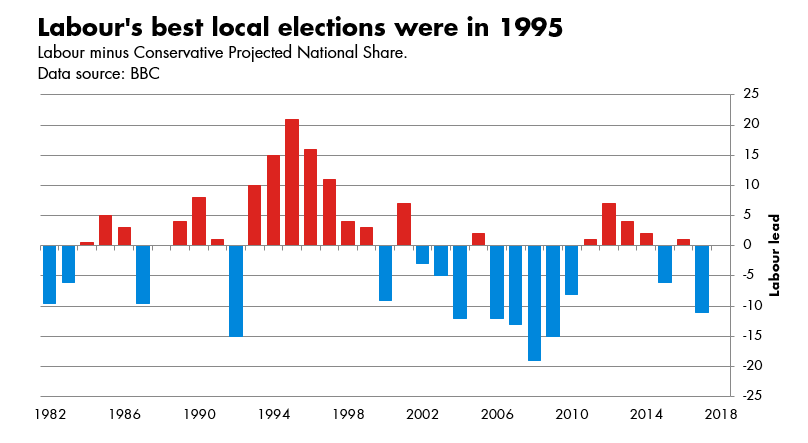

To put these numbers into some sort of context, opposition parties usually win mid-term elections. Labour’s biggest margin of victory came in 1995, and all of the party’s biggest wins were in the 1992-97 parliament. And similarly, the Tories’ biggest wins came in the latter stages of their time in opposition. The following chart shows Labour’s lead over the Tories using the projected national share measure, which for 2018 is zero – a tie:

As 2017 proved, the future isn’t set in stone, and local election results are no guarantee of a future general election outcome. But as polls showed, what happened last year was an unprecedented shift in public opinion during the general election campaign – after the local elections – rather than evidence of a breakdown of the relationship between local and national voting.

As such, ‘par for the course’ for an opposition party in local elections is still to win convincingly on vote share, which at this stage would mean gaining hundreds of seats, rather than the close result last Thursday. Oppositions that have gone on to form governments have done substantially better than this.

If you are prepared to assume that future general election campaigns will always produce decisive swings to Labour, offsetting this ‘governing party’ bias, then the 2018 results would put Labour on course for government, probably in coalition.

If, however, you think that the 2017 general election experience isn’t certain to be repeated, either because the Labour leadership is no longer an unknown quantity to less engaged voters in a campaign scenario, or that the Tories can’t be relied on to implode so spectacularly, then these local election results should be cause for concern from a Labour perspective.

To extend the John Curtice metaphor that local elections are a ‘home fixture’ for an opposition party, this was a home fixture that ended in a goalless draw, against opponents who aren’t playing as a team and seem to be giving the ball away rather often.

Because local elections are not general elections, and people vote differently in each, comparing one with polls for the other can be very misleading. A national tie in the local elections and Westminster polls that put the Tories clearly ahead aren’t mutually inconsistent.

But we can meaningfully compare local election polls to local election results. Granted, these are only available for London. In the capital, Labour was estimated to be 20 points ahead by Survation and 22 points by YouGov, but actually won by 15 or 16 points, depending on how you account for multimember wards. This doesn’t necessarily mean that Labour is doing worse than the polls suggest everywhere, but it should at the very least cast serious doubt on the assumption that Labour outperforming its polls is the new normal.

This is why expectation management wasn’t the real problem. Expectations in London were high for a reason. As Conor Pope has articulated, Labour’s electoral strategy of targeting social liberals, younger graduate professionals and Remainers, means it needs to be making historic gains in the sorts of places where those people live – places like Wandsworth – in order to absorb losses in its traditional areas of support, while still advancing overall.

There are some more encouraging signs for those hoping for a Labour-led government. Labour’s performance in wards with high proportions of renters remains strong. The Conservatives are well aware of their housing problem, but that doesn’t make it straightforward for them to fix it.

And the Tories have other problems of their own. One is that population movements stemming from the housing crisis may well turn the first-past-the-post system against them in the future. Another is their poor performance in battles with the Liberal Democrats which, although not directly beneficial to Labour, could make a Tory majority at Westminster less likely.

Overall, then, last Thursday wasn’t terrible for Labour, but it could have been considerably better. It should be a reminder that there is nothing inevitable about Labour winning the next general election.