Book review: Lost in translation

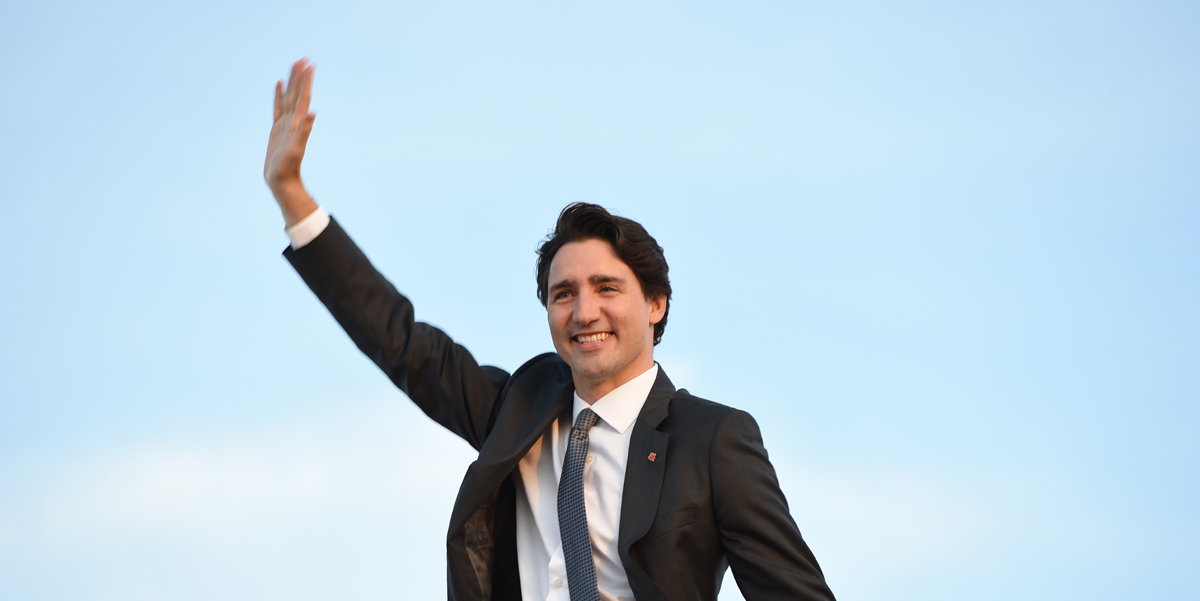

Common Ground: A Political Life, Justin Trudeau, Oneworld, 2017, £16.99 Throughout an eventful 2016, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau was progressives’ most convincing piece of evidence that liberal internationalism wasn’t dead yet. The UK opted to march out of the European...

Common Ground: A Political Life, Justin Trudeau, Oneworld, 2017, £16.99

Throughout an eventful 2016, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau was progressives’ most convincing piece of evidence that liberal internationalism wasn’t dead yet. The UK opted to march out of the European Union. Americans handed Trump a mandate to build a border wall. And for a while it looked as though far-right anti-immigrant leaders might clinch victory in France and Austria.

The Canadian leader, meanwhile, polished his reputation as a poster boy for social progress. Within weeks of taking office in November 2015, he had garnered international media attention for greeting Syrian refugees at the Toronto airport and for appointing a gender-balanced cabinet. Though certainly scripted and stage managed, his outward-looking progressivism wasn’t all for show either. He has continued Canada’s decades-long practice of admitting more than 300,000 immigrants per year, nearly one per cent of the overall population – a greater proportion than any other comparable nation, including Britain. Rightly or wrongly, Trudeau’s success was taken by many on the left as proof that right-wing populism could be defeated. If Canada is any indication, then mass immigration and a declining manufacturing industry are not inevitable precursors to closed-off anti-internationalist sentiment.

Canada’s bucking of 2016’s political trends and Trudeau’s global celebrity status might attract international audiences to his recently re-released memoir, Common Ground: A Political Life. First published in 2014 after he won the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada, the book reads as a coming-of-age story for both a country still in relative youth and its reluctant but somewhat inevitable leader. The 2017 version includes an opening reflective chapter about the Canadian election and his first 11 months as Prime Minister.

As the eldest son of one of Canada’s most controversial but beloved prime ministers, Trudeau details his unconventional childhood growing up in 24 Sussex Drive (Canada’s version of 10 Downing Street). Anecdotes about meeting world leaders and running away from his security detail are entertaining even if they feel somewhat contrived. Chapters on his private education in Montreal and his undergraduate experience at McGill University offer insights into the way that Québec’s linguistic politics manifest personally. Even though Trudeau is fluently bilingual, he is bullied at his French school for speaking unaccented English. Some of his francophone classmates believe that the fact that Trudeau’s English is as good as his French means he is not a real Quebecker.

Common Ground also describes Trudeau’s experimental and somewhat directionless 20s, including a year-long trip around the world before stints as a ski instructor and then a teacher. Throughout it all he takes great pains to dispel his reputation as a silver-spooned dynast. Discussions about the difficulty of his parents’ infamous divorce and his mother’s struggles with bipolar disorder are genuine and touching.

But his story is peppered with predictable and not entirely convincing platitudes about hard work and the need to root out entitlement. By the time Trudeau arrives at his decision to enter politics – an outcome that virtually the whole country had been anticipating since he delivered an eloquent and heart-breaking eulogy on national television at his father’s funeral in 2000 –his claims that he was somehow the underdog in his constituency selection race are almost laughable. He won 55 per cent of the vote against two local candidates. When he ran for leader of the Liberal Party after one term as MP he captured nearly 80 per cent of the vote against five candidates. Trudeau is charismatic and has clearly brought the Liberal Party much success. But that leadership race was a coronation, not a contest.

Common Ground’s narrative is compelling and readable – much aided no doubt by the team of Canadian journalists who have admitted to helping craft it. But Trudeau offers few insights about why an open, internationalist message resonated in Canada when it seemingly floundered everywhere else. His only explanation for Canada’s openness, which he returns to frequently, is an unsatisfying appeal to an apparently inherent and unique Canadian character. He writes: “Diversity is core to who we are, to what makes us a successful country… It has made Canada the freest, and best, place in the world to live.” That may do much to warm the hearts of liberally-minded Canadians like myself but it does little by way of offering a path for other nations to emulate. Embedding multiculturalism as a core national value is a decades long project for which Trudeau fails to offer a blueprint. Britons interested in learning about the personal life and philosophy of one of the world’s most popular politicians will find much to enjoy in Trudeau’s Common Ground. Those looking for translatable political lessons, however, are advised to keep looking.