Eco-fascism on the rise

Coronavirus is not solving the world’s environmental problems – there is nothing to celebrate about the loss of human life, writes Lorna Powell.

The current pandemic is marrying coronavirus and the climate crisis in an unsettling way. A fake XR Midlands account recently tweeted “Earth is healing. The air and water is cleaning. Corona is the cure. Humans are the disease.” The sentiment of this statement has been echoed in videos thanking the lockdown measures for halting transport, lowering air pollution, reducing carbon emissions, forcing people to adopt a slower pace of life and allowing us to reconnect with each other.

It is a tempting conclusion to come to – and searching for silver linings in a global catastrophe that has brought pain, panic and uncertainty is understandable. The yearning to find positives in a landscape of negativity and fear is not, in itself, a culpable act. What is overlooked in this narrative, however, is the human suffering at the heart of coronavirus, both for the victims and their families. Celebrating a reduction in emissions, as a result of a contagious virus that kills the elderly, the poor and those with underlying health conditions is not a silver lining; it is eco-fascism.

‘Eco-facism’ refers to the violent and fascist methods used to achieve environmental goals. On the surface, they arise from a vital and worthy cause – the climate and ecological emergency. However, the means by which eco-fascists are willing to meet climate targets and reduce emissions are worrying.

Predominantly, eco-fascists believe the solution is to curb overpopulation. If the population decreases, carbon emissions will drop and there will be more resources to distribute amongst the remaining people. Historically speaking, this rhetoric is not new. Thomas Malthus, an 18th century economist, warned that if population growth did not slow down, we would not be able to produce enough food to feed the world and we would not be able to end poverty.

Eco-fascism is steeped in white supremacist and colonialist ideologies. Eco-fascists are not looking at population sizes in white, Western countries – they are looking for numbers to fall in African and Asian countries where birth rates are higher. This can be seen, for example, in the stickers produced by the far-right group, Hundred Handers, co-opting Extinction Rebellion branding and bearing the message “third world overbreeding destroys the planet”.

By illogical conclusion, eco-fascists believe that a higher quantity of people, as a result of a higher birth rate, directly correlates with a higher output of carbon emissions and a greater strain on resources. Except this is incorrect, as evidenced in a report by Oxfam in January this year. It takes the average UK citizen five days to emit the same amount of carbon as a Rwandan person does in an entire year. This figure increases to 12 days to equate to the same annual carbon footprint of someone in Malawi, Ethiopia, Uganda, Madagascar, Guinea and Burkina Faso. Yet the Western world, historically responsible for the majority of the damage done to the environment, looks to countries in the global south, which are disproportionately affected by climate change, to pay back its carbon debt in the currency of people’s lives.

Eco-fascism is being woven into the mainstream response to coronavirus. Statements claiming that ‘humans are the virus’ have gained significant traction on social media. The self-awareness required to have reached such a lofty conclusion is both privileged and ignorant. First, it is unlikely that anyone who has lost of a loved one due to Covid-19 believes that ‘coronavirus is the cure’. And, on matters of the planet’s health, this view disregards the ancient practices of indigenous people that show us humans are capable of respecting and working with the land. Indigenous communities have been doing this for centuries and thus humans are not parasitical to the planet, as eco-facists would have us believe.

Online, there have also been more optimistic, free-spirited observations that coronavirus is simply ‘Mother Earth healing herself’ – accompanied by misleading pictures of Venice’s clear canals and smog-free cities. Again, these reflections are both intensely naive and insensitive to the lives of those who have died from Covid-19. Whilst some may come from a good, yet misguided, place, they miss what must be at the heart of the climate and ecological movement: justice for all and less overall suffering.

The coronavirus crisis and the climate crisis should instead be viewed as two sides of the same coin. Both are the product of a deeply globalised and commercialised planet; both highlight gaping flaws in our global economic system and a lack of investment into public services; and both condemn those who benefit least from the system. Climate change disproportionately affects black and brown people in global south communities. It disproportionately affects poor people, refugees, disabled people, the homeless, womxn, marginalised people. As does coronavirus.

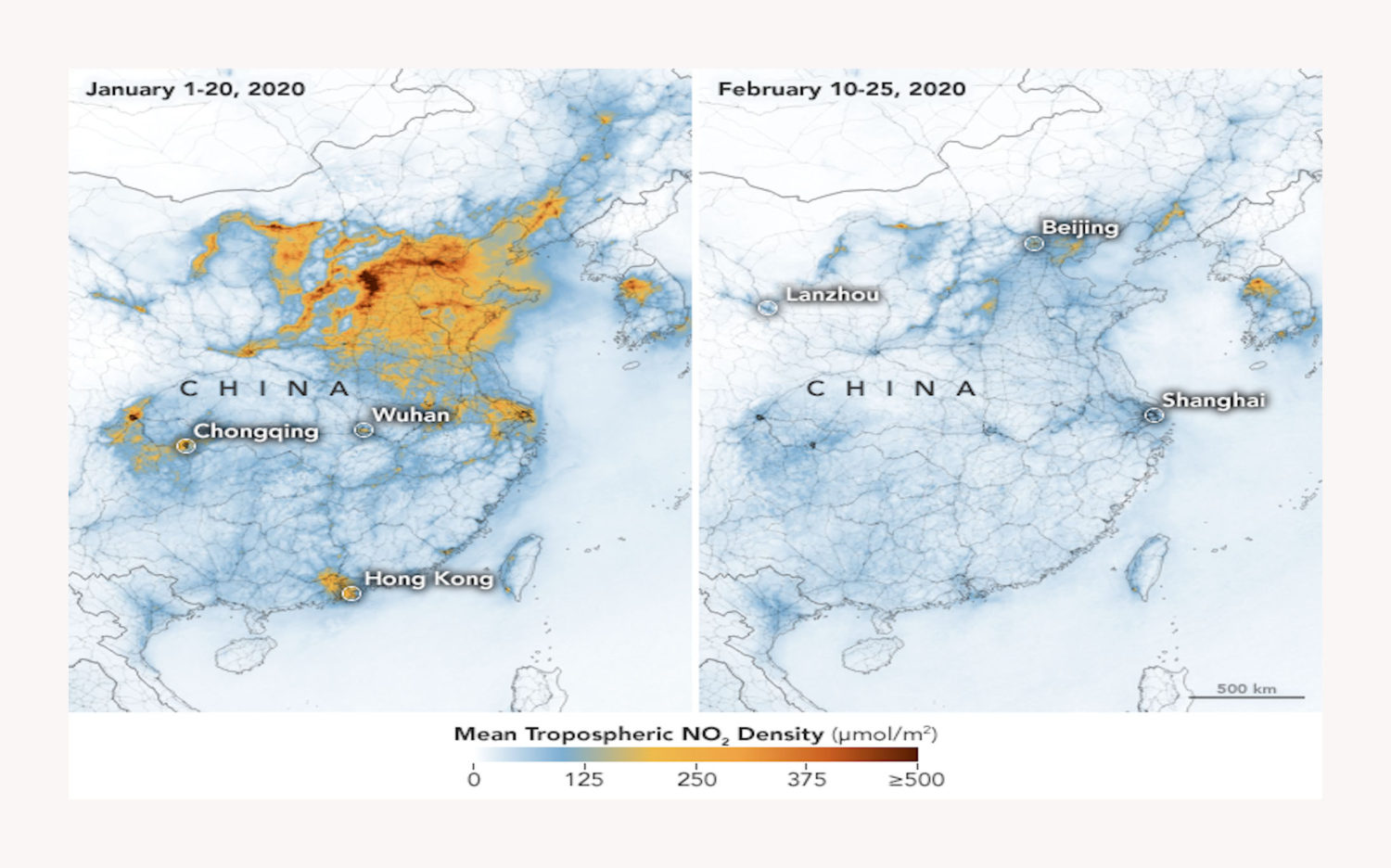

Above is NASA’s satellite image of China’s falling pollution levels during lockdown. It is startling. However, from an environmental standpoint, such improvements are deceptive as they are unlikely to be sustained post-pandemic. In an all-too-common shortsightedness, we have applauded cleaner air without looking at the larger picture. When China starts to rebuild its economy – which it will have to do aggressively, along with the economy of basically every other country in the world – it will ramp up production to make up for lost time and emissions will sharply rise. Li Shuo, a senior policy adviser for Greenpeace Asia, calls this practice ‘retaliatory pollution’. Eco-fascist jubilation that coronavirus is helping us reach climate targets will become grossly ironic when economic targets take priority over the environment as countries start to rebuild. It is likely that climate movements will have to fight even harder to be heard.

Looking forward, it is vital we learn from our response to this pandemic. It has shown that governments and policies can adapt radically to reflect imminent, existential danger and invest in social infrastructure. Communities can gather together to support the most vulnerable. Individuals can adapt to new ways of being and doing, which, in many cases, have been geared towards wellbeing and reconnecting with nature.

Creating a vision of the future that works for people and for planet will require a shift in thought and practice. But climate justice will not be achieved if it is at the expense of human life.

Photo credit: NASA and European Space Agency (ESA) pollution monitoring satellite