Secrecy at Stormont

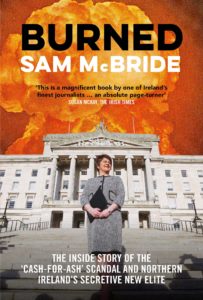

On the day the report into the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme in Northern Ireland is published, Stephen Bradley reviews a compelling account of events.

Burned is the strangely compelling story of the spectacularly inept Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) that led to the collapse of the Stormont’s executive leaving Northern Ireland without government for over three years. But what makes this book so fascinating is the light which McBride casts on a dysfunctional system of sectarian politics and the mess that Northern Ireland is in today.

RHI’s notoriety arose from the lucrative incentives it established for wood pellet burners. Despite replicating almost word for word Great Britain’s legislation, the Northern Irish RHI omitted crucial provisions to cap tariffs. Consequently claimants could earn £1.60 for every £1 of wood chip with no upper limit on claims. ‘Cash for ash’ subsidies were legislated in such lax terms that it proved virtually impossible to stop flagrant abuse and stories of farmers heating empty barns with the windows open abounded. Besides the absurdly counterproductive environmental impact, by the time RHI was finally shut down the scheme had overspent by around £500m, along with the additional £14m cost of the subsequent RHI enquiry.

Much is explained by the venal misconception that Stormont had been written a blank cheque to fund RHI. This delusion of ‘free money’ from Westminster probably accounts for the new-found enthusiasm of the DUP’s climate change deniers for ‘green energy’. McBride also presents convincing, albeit circumstantial, evidence that RHI was promoted as covert state aid to induce the Northern Irish poultry giant Moy Park to expand its operations.

While the evidence falls short of proving that RHI was deliberately set up to enrich insiders, it is clear that numerous DUP figures took an inordinate interest in the scheme with many claiming for burners themselves as well as helping friends and families board the ‘burn to earn’ gravy train.

Despite introducing the legislation as a minister for energy at Stormont and subsequently overseeing the crisis as first minister, the DUP’s leader Arlene Foster has consistently refused to accept responsibility. Instead, Foster, who once boasted of her lawyerly attention to detail, pleaded that she had not read the legislation she brought to the Stormont Assembly. Sinn Féin’s culpability lies mainly in exploiting the crisis for sectarian electoral gain by collapsing the government when the DUP refused to capitulate to entirely unrelated demands, notably for an Irish language act.

Much more interesting than RHI itself is what the subsequent inquiry has revealed about the workings of Stormont and the DUP-Sinn Féin duopoly. In government, both parties comprehensively cowed the Northern Ireland civil service. Civil servants complied with ministers’ wishes that decisions were not minuted and connived with their practice of using personal email addresses for transacting government business. This lack of an official record would later allow Foster and others to shift blame on to their officials. McBride depicts a sycophantic civil service in which standards of impartiality became so degraded that the DUP first minister and Sinn Féin deputy first minister were permitted to hold their own interview for the head of the civil service. Meanwhile, the Stormont Assembly proved entirely incapable of holding ministers to account, in part because its idealistic power-sharing structures meant that for much of the period only two out of its 108 members were not in governing parties.

The role of special advisors (spads) had a central place in RHI. McBride shows that DUP spads were unlawfully imposed on ministers by the party hierarchy and acted as political commissars. In the dysfunctional Department of Energy, Trade and Investment , civil servants frequently took orders directly from spads, who in turn took orders from other unelected party mandarins, bypassing ministerial oversight altogether. In Sinn Féin the influence of such advisors is even murkier. Circumventing a law that barred convicted criminals from working as spads, senior party advisors remained in situ in an unofficial capacity with continued access to Stormont where they continued to manage ministers and officials. Elected politicians in both parties appear to have been little more than public figureheads reporting to the real power brokers, demonstrated by minister of finance Máirtín Ó Muilleoir’s refusal to approve urgent RHI cost control measures for weeks until obtaining ‘sign off’ from his handlers.

Sinn Féin and DUP are not conventional political parties operating in a stable society. They have flourished not by offering sound governance but by posturing as champions of their respective tribes. With both parties tainted by association with paramilitarism it is not surprising that, when tested, they privilege secrecy and triumphalism over democratic accountability. The restoration of power sharing in Stormont is a welcome development but the revelations detailed in Burned suggests that for devolved institutions to provide long term stability, Northern Ireland’s leaders need to be corralled to respect the rule of law and basic norms of integrity and transparency. Given Britain’s own self-inflicted crises, it seems unlikely that a partnership of London and Dublin governments may not be in a position to chaperone Northern Ireland’s institutions to maturity for the foreseeable future.