Dereliction of duty

Proposals to abolish privately funded schools are being actively resisted by the Labour party, writes Steven Longden.

The United Kingdom is at the point of ‘peak’ public schools but not in a manner these misnamed schools would want. Rather, not a month goes by when we are not presented with yet more damning evidence of the negative impact these privately funded schools, incredulously still holding charitable status, are having on the growing levels of inequality in UK society. Indeed, the Sutton Trust has just published research showing that Oxbridge recruits more undergraduates from eight private schools than it does from 2,900 state funded schools.

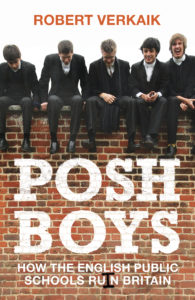

In Posh Boys, Robert Verkaik provides us with a detailed history and explanation of how the private school sector has over the centuries come to dominate all of the UK’s major institutions. Unfortunately, like so many of his predecessors throwing light on this sector, his proposals to abolish privately funded schools are being actively resisted by the Labour party. Despite this, Verkaik has produced a riveting read which is essential for anyone who wishes to see an end to the systemic inequalities perpetuated by the British private education system.

Verkaik’s proposals stand in stark contrast to the Labour party’s timid policy of removing VAT exemption on private school fees. This policy is likely to give most private schools little more than an unpleasant headache: the top tier will easily ride out the removal of VAT exemption with the impact on fee increases hardly being noticed by the countless oligarchs and super rich who are their main customers. Labour’s proposal is not the ‘do not resuscitate’ prescription the 93 per cent of young people not in private schools in the UK deserve in order to secure a more even education playing field.

For only 7 per cent of the nation’s students attend private schools, yet they represent 74 per cent of senior judges, 71 per cent of senior officers in the armed forces, 67 per cent of Oscar winners, 55 per cent of permanent secretaries in Whitehall and 50 per cent of cabinet ministers – the list goes on and on – thanks to the Sutton Trust and the Social Mobility Commission who have been reporting on these inequalities since 2010.

Verkaik highlights the vacuous snobbery of private schools showing that most of the UK’s nineteenth and twentieth-century technological innovations, upon which its economic success and military victories rest, were actually produced by innovators who did not attend private schools. Conversely, Verkaik puts disasters like the huge loss of life in the first world war and the more current Brexit mess down to the “innate sense of entitlement and in some cases almost pathological willingness to risk everything” that private schools delight in inculcating in their students. Think Blair, Johnson and Farage.

Increasingly many Labour party members are looking back to the inspirational achievements of our 1945 post-war government. Huge advances in health, housing and the welfare state were achieved under Clement Atlee’s Labour government and many of these achievements will be reinvigorated under a Jeremy Corbyn-led government. However, Verkaik makes it clear that Atlee is not the leader Labour should look to for inspiration for its proposed National Education Service. In 1946, in a speech made at his beloved Haileybury, where he was privately educated, Atlee stated: “This country changes, but it is our way to change things gradually, and I see no reason for thinking that the public schools will disappear. I think the great tradition of public schools will be extended”.

It is time for the many in the Labour party, predominately those educated in comprehensives and secondary modern schools, to challenge the disproportionately high number of privately educated people in Jeremy Corbyn’s inner circle, including Seumas Milne, James Schneider, Barry Gardiner, John McDonnell, Jon Lansman, Andrew Murray and of course, Corbyn himself. It is time that we put to bed the left’s history of quietly ignoring private education because its leaders are fearful of allegations of hypocrisy and do nothing.

As Verkaik rightly argues, we should not blame politicians for the schools their parents sent them to. But we must make clear that it is a dereliction of duty for a socialist led Labour party to not ensure that it is working across unions and political parties to galvanise support for the phasing out of private education within a two term Labour government – and in such a way that it never returns to these shores. Finland achieved this over a decade in the 1970s and now produces educational outcomes that consistently outshine the UK’s. Finland is a social democracy, so why isn’t the Labour party leadership looking to learn from it on how to phase out private education permanently?