The magnitude of the youthquake

New generations of young adults are more cosmopolitan than older generations. If this trend continues, it will transform the political landscape, write James Sloam and Matt Henn.

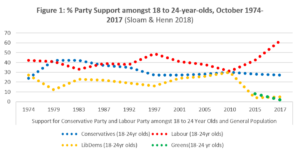

The 2017 UK general election was a landmark vote for young people. Younger citizens turned to the Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn in their droves, as age replaced class as the best predictor of support for the two main parties. The election produced the largest gap in support for Labour and the Conservatives amongst 18 to 24-year-olds for over 40 years, though much of this groundswell in support for Labour can be attributed to a hoovering up of votes from the Lib Dems (preventing any revival after the collapse of their 2015 youth vote) and the Greens (see Figure 1 below).

Youth engagement also increased markedly in other ways. First – and most controversially – in terms of greater turnout. Although youth turnout figures are disputed, most agree that the electoral participation of 18 to 24-year-olds increased to levels not seen since the early 1990s. A British election study report claimed that there had been no major upturn in youth turnout, but was based on a very small sample of 18 to 24-year-olds and had contained large differences between its weighted and unweighted figures. Ipsos MORI and YouGov, using much larger samples of young people, estimated considerable increases of 15 percentage points and 16 percentage points, to 54 per cent and 59 per cent respectively.

Second, after the Brexit referendum there was heightened discussion of politics online and through social media, with over half of 18 to 24-year-olds consuming news about the election through these sources. There was also more intense party activism, with the Labour campaign group Momentum particularly successful in mobilising young activists – this is particularly intriguing given the ‘high cost’ of party activism compared to voting.

Our new book examines in more depth the development of young people’s values and political engagement in the UK, Europe and the United States before and since the financial crisis. We identify the growth of cosmopolitan values amongst younger generations, including a strong belief in human rights, a regard for outward-looking and inclusive societies, and a relatively relaxed attitude towards immigration. Indeed, the best predictor of whether a young person voted remain in the 2016 EU referendum was their support for cultural diversity.

Since the onset of the financial crisis, the divisions in cultural politics have become more pronounced. Political scientists Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart describe Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump as part of a ‘cultural backlash’ against liberal values in society, which has been most prominent amongst older generations, men and those with low levels of educational attainment.

Conversely, many cosmopolitan young people have been mobilised in support of a variety of (socially) liberal causes, movements and parties: from Occupy, to the Spanish Indignados, to remainers in the EU referendum, to support for PoDemos in Spain, Corbyn in the UK, and Bernie Sanders in the United States. It has also benefitted the emergence of young, socially liberal political leaders, including Jacinda Ardern in New Zealand and Justin Trudeau in Canada. The example of Trudeau demonstrates that support for social liberalism does not necessarily equate with heavily interventionist (classically left-wing) economic policies.

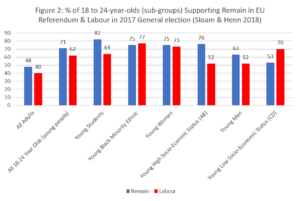

Of course, young people are not all the same. We identify more precisely the demographic profile of these young cosmopolitans, who voted remain in 2016 and for the Labour party in 2017. Figure 2 below shows that young remainers and young Labour supporters represented 71 per cent and 62 per cent of 18 to 24-year-olds in the UK respectively. The figure rises amongst young students (in full-time education), young black and minority ethnic citizens, and young women. The strong support of young women is interesting, given that there was no significant difference between support for remain and leave, or Labour and Conservatives, amongst men and women of all ages. We speculate that this might be a direct reaction to the male chauvinism inherent in high-profile global ‘cultural backlash’ movements: from the derogatory statements about women expressed by Donald Trump, to sustained attacks on campaigns (such as #MeToo) that highlight discrimination and abuse against women. We also note that more young people of low socio-economic status voted for Corbyn in 2017 than supported remain in 2016. The reverse was true for young people of high socio-economic status.

Conversely, there is a significant minority of young people who supported Brexit, who are deeply concerned about national identity and immigration, and who are attracted to authoritarian-nationalist forms of populism. These young people are disproportionately male, with low levels of educational attainment.

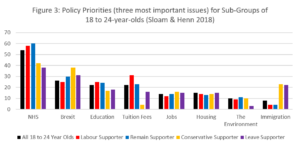

The similarities between young remainers and young Labour supporters in their policy priorities is striking, and illustrated in Figure 3. The NHS was viewed as one of the most important issues by 58 per cent of young Labour supporters and 60 per cent of young remainers, and by only 40 per cent of young Conservatives and 38 per cent of young Leavers (a gap of around 20 percentage points for both). Tuition fees were prioritised by 31 per cent of young Labour and 23 per cent of the pro-EU young remainers, and only 4 per cent of young Conservatives and 16 per cent of young leavers. Finally, only 4 per cent of young Labour supporters and young remainers believed that immigration was a priority (compared to 23 per cent of young Conservatives and 22 per cent of young leavers).

This highlights the immediate challenges facing the main political parties. The findings reveal that Brexit – and the associated issue of immigration – continues to be a theme that will deter young people from supporting the Conservative party. The evidence also indicates that unequivocal Labour support for a second referendum and for continued membership of the EU customs union would enhance its appeal amongst younger voters (particularly students), and offset concerns about its socially liberal credentials in the wake of allegations about antisemitism. However, the party should maintain its focus on addressing problems within the NHS – the issue of mental healthcare is particularly important for young people – and investment in education.

In the UK, young people were outnumbered and outvoted in the 2016 referendum and the 2017 general election, but these two polls illustrated the hardening of intergenerational, cultural cleavages. According to our figures, 61 per cent of over 65s supported Brexit in the EU referendum, and the same proportion of this group supported the Conservative party a year later. The intergenerational divide on cultural issues has major implications for the future of post-industrial democracies. New generations of young adults coming of age over the next decade are not pre-destined to hold more cosmopolitan views than older generations, but – if this trend continues – it will transform the political landscape.

At the same time, there are key challenges on the horizon for the political parties. The Conservative party will struggle to rebuild trust amongst younger cohorts in the wake of Brexit and the intergenerational inequalities forged by a decade of austerity. But Labour has the task of broadening its appeal to young (white) men by convincing them that they have the answers to the economic problems that they face, and that these problems have little or nothing to do with immigration and EU membership.